News of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and its technological developments was rife in the media across 2023 and the increasing impact of this upon the photography world made the Redeye Team keen to find out more.

In mid-October last year The Royal Photographic Society (RPS) hosted: Photography and Artificial Intelligence (AI) conference, with an exhaustive list of photographers and academics giving talks and presentations; we jumped at the chance to attend.

There were many impressive talks, interviews and discussions across the two-day conference – two speakers in particular sparked our interest: Katrina Sluis and Caroline Sinders.

Katrina Sluis is an Associate Professor and Head of Photography at the School of Art and Design, Australian National University where she also convenes the Computational Culture Lab and with Andrew Dewdney, she is the co-editor of The Networked Image in Post-Digital Culture (2022).

Caroline Sinders is an award-winning critical designer, researcher and artist. They’re the founder of human rights and design lab, Convocation Research + Design. They’ve worked with the Tate Exchange at the Tate Modern, the United Nations, Ars Electronica’s AI Lab, The Information Commissioner's Office (the UK’s data protection and privacy regulator), the Harvard Kennedy School and others.

After hearing their talks - Katrina’s: The Photographic Program of AI and Caroline’s: Making Art with Photographs and AI in the Age of Dalle-e (or why photographs, as data sets authored by artists, still deeply matter), we decided to further the conversations with them and sent a few questions for them to answer. Read on to find out what they came back with…

In Conversation with Katrina Sluis:

Photo credit: Katrina Sluis headshot courtesy of Phil Hewitt

Redeye: What was it that sparked your strong interest in AI and led you to researching it?

Katrina: I have been using the internet since I was 13 (before the web had pictures!) so I’ve been interested in the development of image culture online. In the early 2000s I bought my first camera phone and began writing about the ‘turn’ in photography from a print-oriented to a networked, ubiquitous, screen-based, algorithmic practice. During this period, I also became interested in how computer scientists and Web 2.0 venture capitalists were addressing the increasing image glut. I began reading computer science papers on photography, which was so removed from the scholarship I’d encountered in my visual arts studies. It became clear to me that computer science imaginaries were increasingly shaping photographic culture, yet largely absent from discussions of photography. This led me to further engage with scholarship on machine vision, as well as aesthetic computing and start interviewing engineers and researchers. I was fortunate to be able to bring these concerns into my curatorial practice at The Photographers’ Gallery from 2012, when I became its inaugural digital curator. By the time I left in 2019, the gallery had initiated numerous projects, commissions and events around the photographic culture of machine vision, some of which you can read more about in this publication just released by the gallery. As it turned out, this period was incredibly significant in setting the cultural and technical foundations for the development of today’s text-to-image generators such as DALL-E and Midjourney, as I discuss in this recent paper for Critical AI journal.

Redeye: To what extent do you think photographers should be concerned about AI now, or in the future?

Katrina: First, we need to be clear about what we mean by ‘AI’, which is really a marketing term for a set of machine learning technologies. I think there is a danger in characterising generative AI as simply a new ‘tool’, as many photographers do: it forms part of a political economy reconfiguring the relations between seeing and knowing. The novel outputs of text to image generators mask vast computational and human infrastructures which support its production. As we face ecosystem collapse, the computational requirements of training these large language models is extraordinary – communities in the US are now competing with Microsoft (who run OpenAI’s infrastructure) for access to local water. As the artist Hito Steyerl notes, this is a business model that relies on data “kidnapped” from the cultural commons, which is then processed and sold back to the public for a profit. Meanwhile, AI is making decisions about who get jobs, mortgages, who goes to jail. Rather than valorise the output of such models and build Instagram audiences through one’s ‘promptography skillz’, I think the task is to really critically engage with them as systems of capitalist representation. At a time when people are speculating about possible AI model-collapse, it is hard to know what the future of generative AI is: will a shortage of human-generated training data mean that photographers will become ultimately fêted as authentic human producers of AI training data?

Redeye: Is there anything you would like to add, regarding how AI affects photographers and the photography sector, either from your own research or your own broad observations?

Katrina: Many photographers will incorporate generative AI into their workflow, whilst others will no doubt react by fetishizing analogue processes further. With the incorporation of generative AI into everything from word processors to Adobe Photoshop, it appears increasingly impossible to opt-out; even at the level of the camera, machine learning has contaminated the photographic process (from smile recognition to aesthetic evaluation). Since the 2000s there has been a real need to critically rethink photographic pedagogy and approaches to visual literacy – I think with this new turn in computational image-making people are finally grasping this. Cultural institutions have an important role to play, not just in opening up the ‘black box’ of image synthesis for public interrogation, but in supporting progressive approaches to machine learning technologies in the museum that don’t amplify the hype and naturalise it. With this in mind, I recently organised Critical AI in the Art Museum – a series of public events aimed at cultural workers to explore what this might look like, the archive of which is available here.

Photo credit (from Katrina Sluis): Midjourney output: “A group of mourning photographers at a funeral for photography, clutching their cameras, in the style of Annie Liebovitz, —ar 3:2”

In Conversation with Caroline Sinders:

Photo credit: Caroline Sinders headshot by Alannah Farrell

Redeye: For those who are unfamiliar with the term, could you explain what ‘Dalle-e’ is and how it contributes to image-making within AI?

Caroline: Dall-e is a product from a company called Open AI and is an image generator made from generative AI; thus, this begs the question: what is generative AI? Zdnet defines generative AI as “models or algorithms that create brand-new output, such as text, photos, videos, code, data, or 3D renderings, from the vast amounts of data they are trained on. The models 'generate' new content by referring back to the data they have been trained on, making new predictions.” I think generative AI is a bit more complicated than that – in the sense that ‘creating “brand new” work’ depends upon whose definition of brand new and what work is. Generative AI are AI systems that are made up of data and are considered large foundational models that use so much data. What is data? Well, data can be images, text, video, etc. Since Dall-e is an image generator, it’s using all kinds of image and visual based data which can include copyrighted images, large parts of the web, social media, blog posts, etc. While it does ‘generate’ an image, I think this leads to a lot of confusion over ‘creation’, ‘authorship’, and creativity- but as a researcher and photographer, it’s this grey area of confusion I find fascinating. The system is generating an image but there’s so much more to creation and creativity than the output of one image, of one visual.

Redeye: What made you shift from being solely a photographer to a researcher on AI, too?

Caroline: I was also interested in technology even when I was studying photography in my bachelors. For me, I was interested in the intersections of the future of photography, technology and arts communities; I graduated undergrad a year after Instagram launched and I posted a lot of images on Flickr as a photographer. So, I was also interested in the ways in which technology allowed for photographic communities to appear online, and for images to spread and gain notoriety, similar with the rise of popular blogs and blogging. For me, how images were being shared and engaged with digitally was just as important as the images I was making – so this focus really led to my eventual interest in AI, because I’ve always been interested in this triangle of art, society and technology.

Redeye: Is there anything you would like to add, regarding how AI affects photographers and the photography sector, either from your own research or your own broad observations?

Caroline: For me, it’s really important to stress how my photographic practice is a direct part of my AI art practice. I’m often handmaking my own photographic or video data sets that feed into the AI art I make – so I am authoring every step of this pipeline. The ‘data’ is also a key form of art and of the art project, but, the process of making the AI art piece is also a part of the art itself. As photographers, I believe it’s important to allow for collaboration with technology, while still honouring our photographic practices. It’s why I advocate for: consent, credit and compensation in regards to images and copyright, being utilised in large datasets. Meaning, as the author of an image, I should give consent for my image to be used, be given credit and be compensated.

But outside of that, because photography is both an arts and technology practice, I like to highlight how I use both technology and photography as a part of my artistic practice. There’s a lot to critique in Generative AI and there’s a lot to correct in how those tools are currently built. Generative AI is not the AI art I make. I think of the AI art I make as ‘AI enabled art’ and creating a distinction between those two modes of AI is important. I don’t think AI art is ‘bad’ nor can this conversation be had in a binary, but, I do seek to help illustrate how new media art with photography and AI can be an equitable and interesting practice. Meaning, AI can be a tool used by photographers and it can be designed and built to respect an artist’s work, copyright and agency.

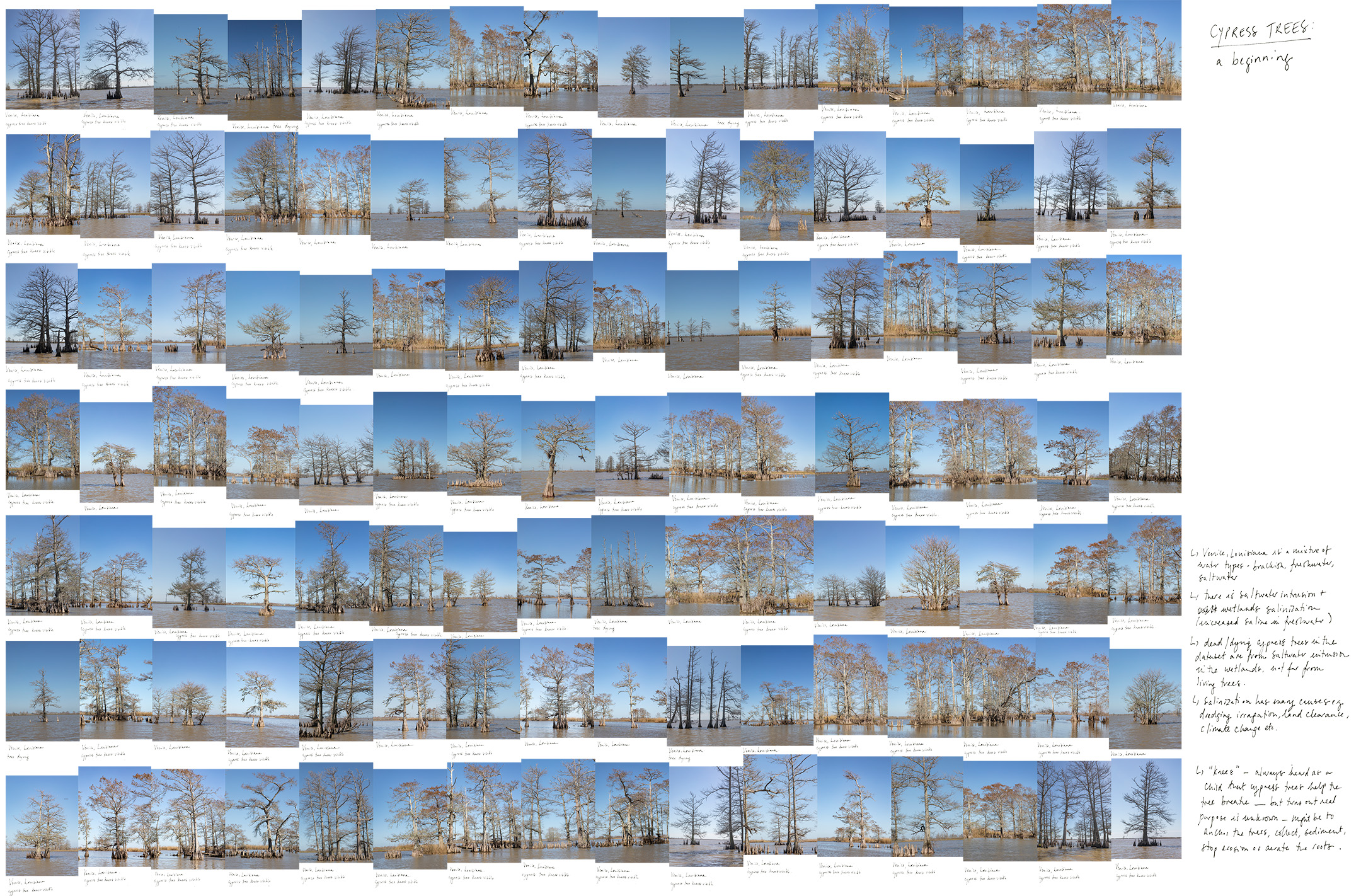

Photo credit:

Cypress Trees: a Hybrid

a collaboration with Anna Ridler and Caroline Sinders.

You can find out more about Caroline and Anna’s work here:

https://www.instagram.com/carolinesinders/

https://www.instagram.com/annaridler/

AI and its relationship to photography is broad and constantly changing – we’re pleased to have furthered our understanding of the technology by attending The RPS’ Photography and Artificial Intelligence (AI) conference and having spoken further with both these specialist experts in the field. Be sure to check out their work if you wish to learn more and you can find out more about The Royal Photographic Society and their other upcoming events here.